We are all familiar with the story of The Flood in the Hebrew Bible. But this is not the first account of a catastrophic near-extinction event in recorded human history. The Mesopotamians who lived centuries before the book of Genesis was written had their very own captivating flood story similar to Genesis in many ways, but told in the style and traditions of their own rich and unique culture.

We are all familiar with the story of The Flood in the Hebrew Bible. But this is not the first account of a catastrophic near-extinction event in recorded human history. The Mesopotamians who lived centuries before the book of Genesis was written had their very own captivating flood story similar to Genesis in many ways, but told in the style and traditions of their own rich and unique culture.

The Biblical Account

This flood story is a smaller narrative within a larger epic. The epic “The Five Books of Moses” recounts all that had occurred from the beginning of creation leading up to the birth of the nation of Israel. A summary of the flood, the proverbial tale within a tale, is taken from the reference at the end of this post (1). I know most readers know this story backwards and forwards, but bear with me and refresh your memory, because reviewing this version will help in comparing it to the Mesopotamian version.

As the years passed, people began to fill the earth. But when God saw that man’s wickedness covered  the earth, and that every imagination of his heart was only evil continually it grieved the Lord.

the earth, and that every imagination of his heart was only evil continually it grieved the Lord.

And the Lord said, “I will destroy mankind, which I created, from the face of the earth.” But the Lord looked on Noah with favor. Noah, a righteous man, perfect in his generations, walked with God.

So God said to Noah, “The end of all mankind is coming. Because people have filled the earth with violence, I will destroy them along with the earth.

Make yourself an ark of wood. Build rooms in it and cover it with tar, inside and out. Build the boat four hundred and fifty feet long, seventy-five feet wide, and forty-five feet high, but make only one  door.

door.

You, your wife, your three sons and their wives must go into the ark. Bring also a male and female of every animal into the ark, to keep them alive with you.

Two of every sort will come to you, but you must take by sevens all the animals which I have declared holy.”

While building the ark, Noah preached to the wicked people, saying; “Those who refuse to honor God shall be destroyed.” Sadly, everyone mocked Noah and laughed at God’s warning.

But Noah and his family believed God, so at the appointed time they entered the ark, and the Lord shut them in.

Then God caused it to rain on the earth for forty days and forty nights. From underground, water spouted up like fountains and the waters increased on the earth. The waters kept rising, until the ark floated.

Finally, the water covered everything on the earth, including the hills and even the mountains.

Birds, cattle, walking and crawling animals, and every person on earth—all were destroyed, drowned in the flood.

The waters covered the earth for one hundred and fifty days. But God took care of Noah and every living thing in the ark. Then God made a wind to pass over the earth causing the water level to begin to go down. The waters continued to recede from the earth.

When the ark came to rest upon the mountains of Ararat, and the plants began once again to grow,  God spoke to Noah, saying, “Go out of the ark, you and every living thing with you.” And they went out.

God spoke to Noah, saying, “Go out of the ark, you and every living thing with you.” And they went out.

Then Noah erected an altar and offered a sacrifice to the Lord.

Afterward, God blessed Noah and his sons, saying to them, “Be fruitful, have many children, go out and refill the earth. Also, besides the plants I gave you for food, animals are now delivered into your hands to eat. But anyone who kills another human being must forfeit his own life, because man is made in the image of God.”

Then God said, “Behold, I am establishing My promise with you, and with your descendants after you.  Never again will all people and animals die from a flood.

Never again will all people and animals die from a flood.

I am putting My rainbow in the clouds as a token of My promise.

Whenever I bring rain clouds over the earth, you will see the rainbow, and I too will see it, and honor My covenant.”

The exoteric moral is that God, in his mercy, weeded out all the irreversible corruptions of mankind that were generated because of abuse of free will; then He replanting new seeds which were more amenable to His cultivation.

The Mesopotamian Account

In the Hebrew counterpart, this story is a smaller narrative within a larger epic called the “Epic of Gilgamesh”. Gilgamesh was a historical figure in 2700 BCE. He was an actual King of Mesopotamia of great influence and physical strength who later became memorialized in mythology as “one third human and two thirds deity”. Whereas his mortality was inherited from mankind, his supernatural strength was inherited from the gods. Unlike the Egyptians and Hebrews from a later error who learned to write on parchments, Mesopotamians told their history and legends by pressing then into cuneiform letters onto clay tablets. The Epic of Gilgamesh was discovered on twelve tablets. Each tablet contained one episode of the epic legend.

According to myth, Gilgamesh was a great builder and protector of the material parts of his kingdom, but cruel and insensitive to its inhabitants. Like the Greek Odysseus, he departed his kingdom on a series of adventures which changed him for the better and prepared him to be a better king at the end of the epic.

During the course of these adventures, his best friend Enkidu died after telling Gilgamesh a nightmarish vision about the bleak and empty afterlife waiting for the dead. Gilgamesh vowed then to search for the secret of immortality, a quest that then tool him to realms far, far away beyond the normal earthly realms. There he meets a holy man named Utnapishtim. This holy man had the reputation of obtaining immortality as a result of his experience during the great ancient Flood.

I recommend getting a feel for this epic by watching this 10 minute animated presentation, “The Epic of Gilgamesh An Animation” (2).

For the more ambitious of heart, either before or after reading this post, check out this excellent one hour lecture by the gifted professor Ed Greenstein at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, entitled “The Gilgamesh Epic and its Interpretations” (3).

The following is a summary (4) of the flood account in the eleventh chapter of the epic:

Gilgamesh, having lost his close friend, Enkidu, turns his desire to immortality. He does not want to experience the dark, mindless existence of sheol (the netherworld, the Greek Hades). He knows of a man who has become god-like and immortal, who survived the great flood. Gilgamesh journeys to meet Utnapishtim and learn from him the secret of immortality.

Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh the story of the flood. He wants Gilgamesh to know that his immortality was something granted by the gods and is not achievable by Gilgamesh.

In the council of the gods, it was decided to destroy humankind and all living creatures on earth. It was in Enlil’s heart to do this. Enlil was one of the chief gods of Sumeria.

Ea, another powerful god also known as Enki in Sumerian, wanted to save his beloved Utnapishtim. He did not wish to rebel against Enlil, so he whispered to the walls of the hut in which Utnapishtim was sleeping a warning about the flood and instructions to build a giant structure to float in the deluge (the dimensions are much larger in the Mesopotamian account).

Utnapishtim built the huge vessel, animals came to him, and he received warning from one of the gods when the time was right to enter the vessel and ride out the flood.

The storm god Adad unleashed a great storm on the earth and was aided by Irragal, Ninurta, and Anunnaki in causing the waters to flood in a wrathful deluge that ended all life. Other gods, such as the goddess Istar, were terrified and fled to the highest heaven to escape this killing flood.

The rain came six days and nights and abated on the seventh day. The flood receded six days and nights. The great vessel became lodged on Mt. Nitzir. On the seventh day, Utnapishtim sent out a dove to see if there was dry land. The dove returned. He then sent a swallow and it returned. Finally he sent out a raven, which did not return and he knew there was enough dry land to exit the vessel.

Utnapishtim made an offering to the gods. They came hungrily like flies and swarmed around his offering. A dispute broke out. Enlil sensed that is was Ea who caused the saved people and animal to live. Ea argued for Utnapishtim’s life and Enlil touched the hero’s forehead and said, “Hitherto Utnapishtim was a man, but now Utnapishtim and his wife shall be like us, the gods.”

In the remaining epic, after hearing the flood story from Utnapishtim, Gilgamesh returned to his kingdom, glad to be home, but humbled by his adventures and coming to terms with his mortality. He learned to put less value on greatness, which is fleeting, and focused more on being a king who is good to his people. This required him to develop other skills besides physical strength. The exoteric moral of the epic is that even though man is mortal, he may attain some measure of immortality through the positive contributions to mankind he leaves behind, often accomplished more by virtue than by shear strength.

Which Came First?

No one knows for sure which narrative came first, Biblical or Mesopotamian, or whether they were both derived from a more ancient narrative. Even though the Biblical account was written using the later developed technology of parchments, it may have been preserved by the Hebrews as part of their oral traditions long before then. Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Hebrew cultures were known to infuse with each other through migration and trade.

So which came first, the chicken or the egg?

So which came first, the chicken or the egg?

In answer to the question of whether the Biblical or Mesopotamian narrative came first, Christian apologist Frank Lorey (5) leans toward the biblical account as more original and authentic:

“To those who believe in the inspiration and infallibility of the Bible, it should not be a surprise that God would preserve the true account of the Flood in the traditions of His people. The Genesis account was kept pure and accurate throughout the centuries by the providence of God until it was finally compiled, edited, and written down by Moses. The Epic of Gilgamesh, then, contains the corrupted account as preserved and embellished by peoples who did not follow the God of the Hebrews.”

Personally, I think if the bible is inspired and infallible, then Frank Lory’s statement creates sort of a paradox for me, because the bible looks down on subjective rationalizations. Such backsliding marked the continual downfall of most of the Kings of Israel and Judah, who were always finding justifications for doing it “my way” instead of heeding the directions and warnings of the prophets. Biblical apologetics seems like an oxymoron to me. It has a noble cause of “defending the faith”, but actually defends subjective rationalizations.

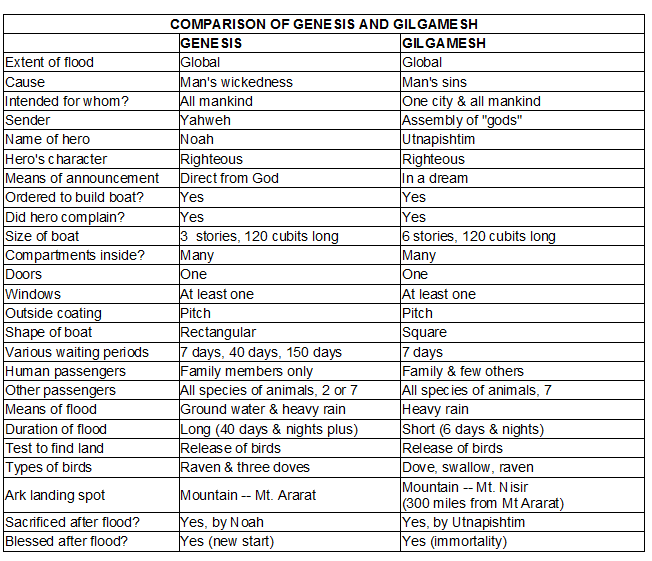

Comparison Chart

I have learned that SOS readers value comparisons made with concise charts, so I have expanded on one provided by Frank Lorey comparing the Biblical and Mesopotamian Narratives. The similarities are striking.

Conclusion

There are a lot of similarities in the two narratives. Who is to say which is more authentic? Both have exoteric and esoteric meanings. I summarized the exoteric ones. There have been previous SOS posts describing the esoteric meanings of the biblical flood. Combining knowledge of the two narratives might provide more insight into both.

REFERENCE SOURCES:

- Noah and the Great Flood, Parts 1 and 2, (a summary of Genesis 5:31-10:1), http://christiananswers.net/godstory/flood1.html

- http://christiananswers.net/godstory/flood2.html

- The Epic of Gilgamesh An Animation, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qOrfrHys8g8

- The Gilgamesh Epic and its Interpretations, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aWkR3QowdI

- The Noah Story and Mesopotamian Myth, Parts 1 and 2 http://derek4messiah.wordpress.com/2009/10/20/the-noah-story-and-mesopotamian-myth-pt-1, http://derek4messiah.wordpress.com/2009/10/20/the-noah-story-and-mesopotamian-myth-pt-2

- The Flood of Noah and the Flood of Gilgamesh, by Frank Lorey, http://www.icr.org/article/noah-flood-Gilgamesh

Robert,

You’ve given us something interesting to ponder here. Personally, I believe the Epic of Gilgamesh to be older. I studied a little bit up on both in graduate school.

It would be very interesting to see an esoteric interpretation of the Epic of Gilgamesh. I don’t have the time now, but maybe someone else will get interested enough to look into the matter.

Thanks Josh,

I also believe the Epic of Gilgamesh to be older in terms of being a documented narrative. The fact that they were written in stone attests to this. The Five Books of Moses were not documented until much later, as late as the winding down of Babylonian captivity. The Sumerians and Abraham came from the same area in what is now Iraq and so Abraham might have carried the undocumented account of a flood with him to Caanan. It’s hard to know for sure. Sumerian influence also reached the Caananite tribes.

Esoteric interpretations of the Epic of Gilgamesh are available online by googling “Esoteric interpretation of the Epic of Gilgamesh” if anyone wants to research these or summarize then in a post.

Blessings,

Robert